Dominika Laster

Short bio

Dominika Laster – theater director, writer, Associate Professor of Theatre and Performance Studies at the University of New Mexico. She holds a PhD in Performance Studies from New York University. She is the Books Section Editor of TDR: The Drama Review (TDR) and Co-Editor of European Stages. From 2013-2015, she served as the Director of Undergraduate Studies and Lecturer in the Theater Studies Program at Yale University. She was a Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Interdisciplinary Performance Studies at Yale (IPSY) from 2011 to 2013. She is the curator of Decolonial Gestures: A Symposium on Indigenous Performance (2016) and Performance in the Peripheries. She is the author of Grotowski’s Bridge Made of Memory: Embodied Memory, Witnessing and Transmission in the Grotowski Work (2016). She is the editor of Loose Screws: Nine New Plays from Poland (2015). Laster has also published articles in Performance Research, Slavic and Eastern European Performance, New Theatre Quarterly, and TDR. Currently she is a U.S. Fulbright Scholar conducting research on Yiddish cultural expression.

You were a lecturer in the Theater Studies Program at Yale University and are a recipient of the prestigious Fulbright scholarship. In your everyday life, do you consider yourself primarily a researcher, or maybe also an artist and activist? How can these roles interconnect?

This is a very interesting question: when we think of ourselves, what categories of identity surface? I often think about this myself.

At best, disciplinary categories can function as a useful shorthand. Where they can be dangerous is if we use them to limit—or restrain—how we think of ourselves and others.

One of the things I love most about the field of performance studies—which has been formative for my thinking and doing—is that it allows me to reinvent my research modality or artivist practice each time anew. When I approach a question or a problem, I can ask: what does this particular situation require? And draw on a wide variety of tools across a range of fields and disciplines. In that sense, the term “postdisciplinary” makes sense to me.

In your projects, themes of memory and expression (i.e. of identity) keep coming back. Where does the interest in these particular issues come from?

In truth, I don’t remember. After all, memory is—at its core—a dialectic between remembering and forgetting. While I cannot trace all the points of origin for my interest in memory, here is what I do remember:

As a graduate student, I was very lucky to have the opportunity to work with numerous incredible professors. For instance, I took every possible class with Ann Pellegrini, which explored the intersections of performance and trauma through the lens of psychoanalysis. The same is true for Diana Taylor’s courses on trauma, memory, and performance—one of which was co-taught with Marianna Hirsch through a consortium with Columbia University. (Hirsch is perhaps best known for having coined and theorized the term “post memory.”) I was certainly inspired by these extraordinary scholars and my interest in memory studies was firmly established.

At the same time, many of the discourses on memory I was encountering struck me as highly theoretical, and not sufficiently embedded in practice. I thought that Grotowski’s thinking about and practical engagement with what he called “body-memory”—which predates much of the current discourse on the memory of the body—had a lot to contribute to the conversation.

One of your research projects revolved around the events of 9/11. Could you tell us more about it?

I was living in New York City at the time of the attacks. I vividly recall that day as well as its immediate aftermath. The fallout of those events was both varied and wide-reaching. One of the things that struck me the most in those early days was the speed with which people lashed out against the perceived other: Arabs, Muslims, and those who were mistaken for them—even Sikhs and Israelis. It was a veritable confoundment of identities. I witnessed numerous acts of hate speech and violence against Muslims. Walking to work one day, I saw a Muslim man exiting a mosque beaten by two other men with a metal pole at the end of which hung an American flag. I don’t know what happened to him.

My research grew directly from these and similar experiences. I wanted to better understand the mechanisms by which processes of othering occur and how they lead to hate and violence. I was thinking alongside theorists of various models of abjection such as the Bulgarian-born philosopher and psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva and—another one of my professors—Karen Shimakawa. The project grew to be quite expansive and involved fieldwork with Muslim communities in the US, Morocco, and Saudi Arabia. The result of some of this research and thinking was published in 2008 in Performance Research under the title Bearing Witness to the (In)visible: Activism and the Performance of Witness in Islamic Orthopraxy.

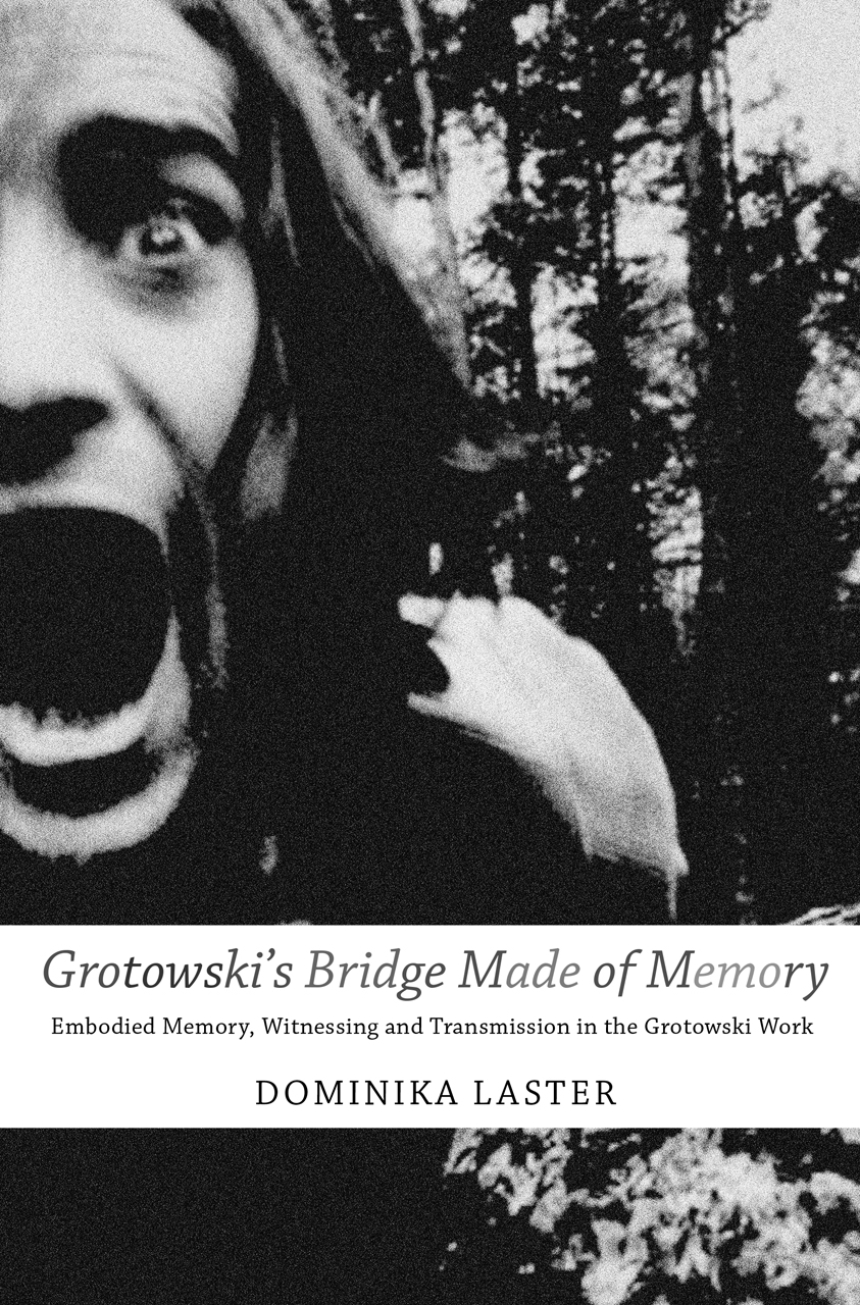

You also refer to the issue of memory—both personal and cultural—in your book dedicated to aforementioned Jerzy Grotowski (Grotowski’s Bridge Made of Memory: Embodied Memory, Witnessing and Transmission in the Grotowski Work, 2016; Polish edition: Most pamięci, 2023). What, apart from your education, made you look at this legendary figure from such a profiled perspective?

I had followed Grotowski’s work for most of my life, however it was never a subject of scholarly interest for me. I had a strong interest in his research for its import for me as a human being. As a result of various circumstances, some of which I describe in the preface and introduction to my book, I had relative proximity to the work. Things shifted in 2009, when UNESCO designated that year as the “Year of Grotowski.” Richard Schechner invited me to collaborate with him on the curation of a year-long series of events in New York exploring Grotowski’s work. Over the course of our work together that year, he continued to persuade me to write my dissertation on Grotowski. And I eventually let myself be persuaded.

The work and research that I had done up to that point in my graduate studies certainly shaped the framing for the work. My aforementioned interest in memory carried over.

Can the metaphor of the “bridge of memory”, which you use to describe Grotowski’s creative practices, be transplanted to other areas of culture, not only Polish? If so, where?

As any Grotowski aficionado will tell you, Grotowski was not a fan of metaphors. In my book on Grotowski, I source that image from Thomas Richards—the person Grotowski designated as his “universal heir”—and try to use that figure precisely and in reference to something very specific. Of course, the image itself is extremely evocative. It can certainly activate our imagination and be mobilized in infinite ways. From an intercultural or political standpoint—to put it concisely—I would say: build bridges instead of walls.

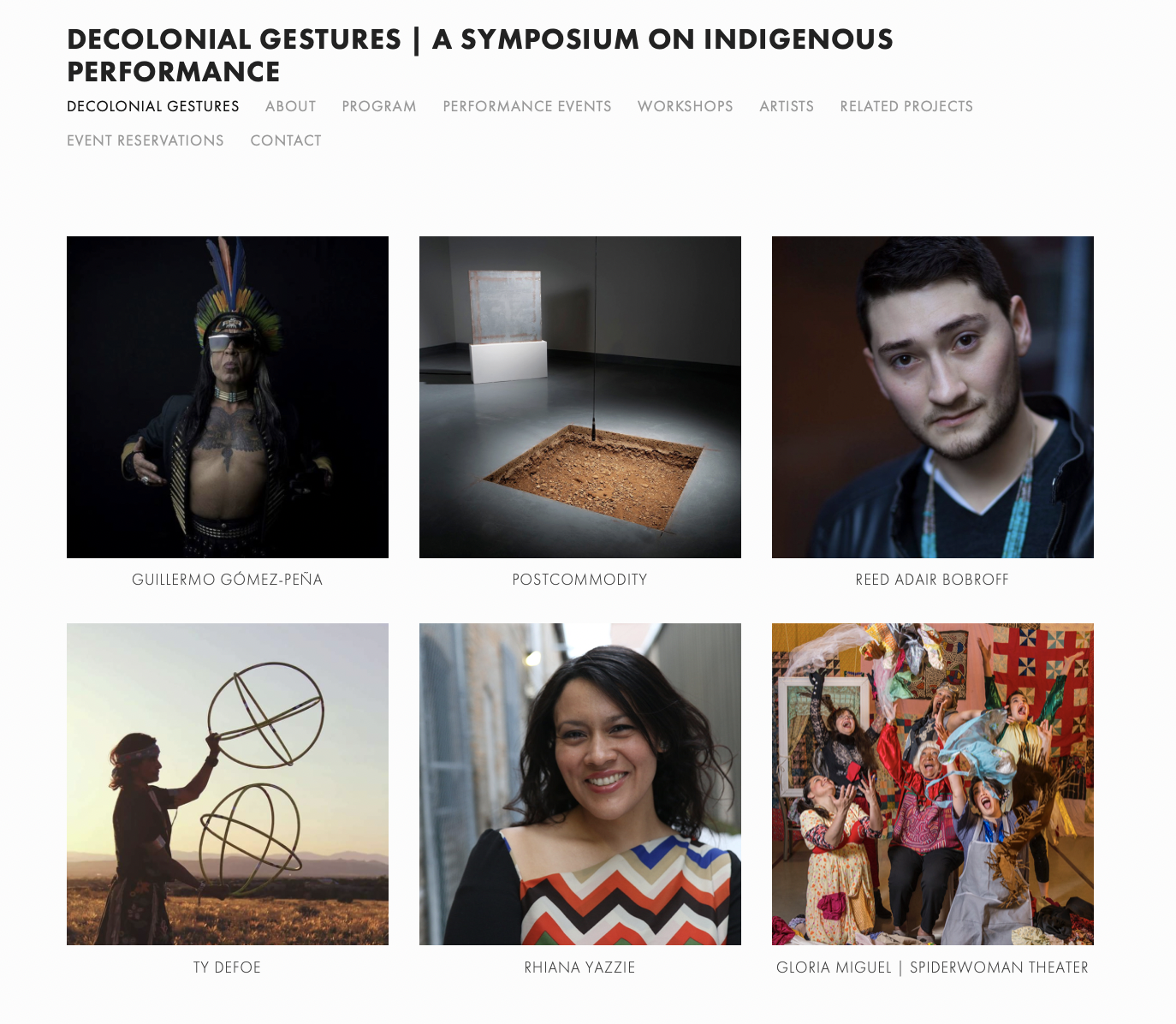

In the past, you also dealt with contemporary Indigenous art and its decolonization—I am referring to the project Decolonial Gestures: A Symposium on Indigenous Performance (2016). Can you tell us more about the idea behind it, the people involved, and the effects it brought?

In 2015, I accepted a job offer at the University of New Mexico and began living and working on the unceded, ancestral lands of Tiwa peoples—colonially known as New Mexico. These Indigenous territories are presently home to twenty-three tribes—nineteen Pueblos, three Apache tribes, and the Diné (Navajo) Nation. While all of North America, and the entire continent for that matter, is Indigenous, Native presence is very visible and palpably felt in this region of the southwest. When I began teaching in the Department of Theatre and Dance, I quickly realized that we had no content in our curricula about Indigenous theatre, performance, ritual, ceremony, or expressive culture. My Native students were learning about Ancient Greece as the source of theatre. Clearly this needed to change. I overhauled my courses to integrate material about Indigenous performance—present and past. But that was not enough, I felt. At the time, I had little expertise in Indigenous performance and could not reinvent myself overnight. So, I decided to organize a symposium on Indigenous performance and applied for a large grant. I invited the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) Museum of Contemporary Native Arts (MoCNA) in Santa Fe to collaborate with me.

The symposium was ambitious—both in design and scope—as it spanned two cities—Albuquerque and Santa Fe—and included three generations of Native artists representing eight different Indigenous nations. The events included a film screening, performances, numerous workshops, and one lively roundtable discussion with all the artists. I very intentionally wanted to avoid dry panels with talking heads. The program featured both established and emerging artists—all truly phenomenal. Among them were Gloria Miguel one of the founders of Spiderwoman Theater (now in her late 80s); legendary performance artist, writer, and MacArthur award-winner Guillermo Gómez-Peña; two-spirit interdisciplinary artist and Grammy award-winner Ty Dafoe. Another one of the symposium guests, composer, musician, and artist Raven Chacon—went on to win the Pulitzer Prize and the MacArthur award.

A very talented young Diné writer and spoken word artist Reed Adair Bobroff made a strong impression with his solo performance, which he called a “one people show” to accentuate the importance of community in Indigenous epistemology. I distinctly remember the 400-seat theatre filled with people, many of them Native, and their felt responses to Reed—alternating laughter, audible sighs, cheering, and applause. It’s as if—for a moment—we were one living organism acutely attuned to this intelligent, sensitive, vulnerable, funny, warm young man onstage.

Overall, it was a beautiful, joyous gathering but also one which did not avoid difficult conversations about coloniality and its enduring aftermath.

The effects of those events are many and varied. It brought communities together. It allowed Indigenous students and community members to see themselves represented onstage. It brought three generations of Native artists together—some for the first time—into a shared space of dialogue and collaboration.

It paved the way for more Indigenous art and artists in the department. Two years later, the department staged an MFA thesis play “1N2IAN” (Indian) by Jay B. Muskett (Diné). As far as we know, this was the first instance of a performance with an all-Native cast since the founding of the university in 1889! We now also regularly offer a course on Indigenous storytelling taught by Diné theatre director Kimberly Gleason. Almost a decade later, we are attracting Native students from as far as Hawaii—desiring to study within a context where Indigenous performance is recognized.

For me personally, the symposium was an opening to sustained and long-lasting collaborations with Native artists. I have also since delved more deeply into decolonial theory and practices of decolonialization and have published on the subject—mostly recently in Global Performance Studies journal.

You are currently researching Yiddish expressive culture. Where did the idea to tackle this particular topic come from and what is your project about?

The impulse comes from a desire to learn about my own story within a larger historical and cultural frame. I discovered that I was Jewish when I was sixteen. Looking back, I recognize the almost complete absence of anything Jewish in the surroundings of my early childhood. I have a vague recollection of walking past a dilapidated synagogue in my hometown of Wrocław. Is it a memory or a fantasy? I remember being shocked when, as a young person, I first watched the 1936 film Yidl Mitn Fidl. The movie, filmed in Warsaw, is entirely in Yiddish and portrays glimpses of the lives of Polish-Jews before the second World War. I was astounded. Why had I not known about the existence of this world?

On the one side, the absence of that world, on the other its specter held tenderly in celluloid. I am driven by a desire to know more about the Polish-Jewish lifeworlds of the then and the now.

I am entering territory that is unknown to me without overdetermining what I will find. Luckily, I am in good company. There are many others recovering stories that have been forgotten, buried, or lost. There are also many others who are building that life in the here and now. I am joining their efforts.