-

20 June 2519:00

Opening of the 9th edition of FestivALT | Shabbat by the Vistula River | Concert | FestivALT 2025

Read more -

09 December 2419:00

Musical Premiere of the Project “Hirsh Lejb Bakon: Cantor from Chrzanów

Read more -

11 December 2418:00

Lecture – Hirsh Lejb Bakon, cantor from Chrzanów

Read more -

29 December 2419:00

A Lichtiger a Hanukkah with Galicyaner Melodies

Read more

Hirsz Lejb Bakon: Cantor of Chrzanów is a collaborative project by the FestivALT Association and the Municipality of Chrzanów, carried out in cooperation with local cultural institutions (the Irena and Mieczysław Mazaraki Museum, the Chrzanów Public Library, and the Chrzanów Municipal Center for Culture, Sports, and Recreation). The project is supported by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (KPO) and the NextGenerationEU fund.

The story of the Chrzanów-based cantor and his legacy is being explored and shared through various initiatives: the results of historical and biographical research are presented online (below) and during a dedicated lecture; a concert featuring compositions inspired by Bakon’s works is being performed in new arrangements by Mojše Band and cantor Rachel Weston; and the pieces are being published online as professional recordings.

Hazans and cantorial music

The figure of the cantor as an officially employed and paid professional first appears in the 7th century, long before the invention of printing. Knowledge of the Hebrew language and access to the prayer book (siddur) make cantors not only performers of prayers, but also their intermediaries.

The growing prestige of this profession means that over time, cantors are expected not only to possess musical skills but also to have a solid understanding of Jewish law (Halacha) and impeccable conduct. Their role is to transform the relatively unchanging structure of liturgical rituals into an aesthetically pleasing and highly emotional experience, reflecting—especially in Eastern Europe—the shared concerns of the Jewish community.

Cantorial music began to develop as early as the 16th and 17th centuries. By the 19th century, cantors performing in synagogues represented the elite of local Jewish communities. Their exceptional status was influenced by their recognition as professional artists, and their compositions drew inspiration not only from European classical music and German Romanticism. The performance styles of traditional liturgical musical motifs (nusach) among Eastern European cantors were also shaped by folk and liturgical music from Russian, Greek, Armenian, and Hungarian traditions.

While cantors originally represented the congregation, leading prayers on their behalf, some of them went on to become recognized artists beyond their local communities. They performed their compositions not only in synagogues but also in operas and concert halls. The first cantor to have his works recorded and to achieve star status was Gershon Sirota (1874–1953), cantor of Warsaw’s Great Synagogue. His rendition of Hashem Malach is now regarded as a standard of cantorial music.

Hashem Malach performed by cantor Gerszon Sirot

The first half of the 20th century was the so-called golden age of cantorial music. As Jeremiah Lodkwood explains:

Cantorial music of the Golden Age represents a revival and popularization of melodies that had previously been regarded merely as the folkloric roots of Jewish music. It was characterized by the contributions of small-town bal tefiles (prayer leaders), Hasidic religious music, and the loud heterophony of davenen (intoned prayer texts), transformed into musical works of art under the influence of operatic music and performed by singers with tremendous expressiveness.

1.Wendy Heller, Cantors – YIVO Encyclopedia

Until the outbreak of World War II, listening to prayers performed by cantors was a common practice in cities with Reform synagogues, both on the Sabbath and during other important Jewish holidays. Ashkenazi Jews developed a uniquely Eastern European form of Jewish prayer known as hazzanut (Yiddish: chazunes).

Due to their high artistic quality, performances by cantors and their choirs in synagogues often served as a primary source of entertainment for many Jewish people—sometimes “the line between entertainment and prayer became blurred.”

Although “practically every synagogue employed musicians who created their own interpretations and arrangements of ancient melodies,” accessing their sheet music today poses a significant challenge. Gershon Ephros (1890–1978), a composer from Serock, played a remarkable role in preserving the cantorial heritage of Jewish music. His six-volume Anthology of Synagogue Music includes not only his own compositions but also works from various regions and eras. In the fall of 2023, as part of the project The Musical World of Gershon Ephros, some of these pieces were performed in Poland for the first time since World War II.

According to Yossi Notkowitz, a producer of cantorial concerts, the 1980s marked the beginning of a renaissance in cantorial art, which continues today, shifting its performances from synagogues to concert halls.

Due to the Holocaust, as well as the frequent mobility of cantors—who often held positions in multiple synagogues during their lifetimes—and the scarcity of biographical information about them, the only remnants we have today are scattered anecdotes, sheet music, or, with some luck, preserved recordings of specific performances.

Against this backdrop, the cantorial legacy of the Bakon family stands out as truly extraordinary.

Bakon Family

According to the etymology of the surname Bakon, it is borne by the “sons of the holy and martyred” (Bne’l kdoshim ve’nitbakhim in Hebrew). The history of the cantorial Bakon clan begins in Kolbuszowa, a town in the Subcarpathian region of Poland, and weaves its way through Tarnów, Kraków, Chrzanów, Berlin, Cluj-Napoca, Košice, Johannesburg, New York, and Israel, as well as Bełżec and Auschwitz. Thanks to the multigenerational musical legacy that has endured and is being revived through this project, war and the Holocaust did not mark the end of this story.

Following in the footsteps of his father, Chaim, his son, Szlomo Reuben Bakon (1899–1986), born in Trzebinia, continued the family’s cantorial tradition. He began by accompanying his father in his choir but later performed independently in Cluj-Napoca. Although his performances at the local opera were highly acclaimed by audiences, he ceased them at his father’s explicit request. Chaim also successfully opposed the idea of his son performing at the Bucharest Opera.

From present-day Romania, Szlomo Reuben emigrated to the United Kingdom before eventually settling in South Africa. For many years, he served as the cantor in Yeoville, a district of Johannesburg, and as the secretary of the Cantorial Association in South Africa.

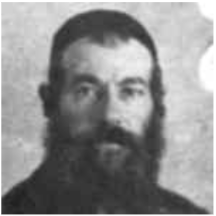

Hirsz Lejb Bakon (1875-1928) cantor, chazzan

Rachela Fajga Bakon (1877-1943), wife of Hirsz Lejb Bakon

¹ Por. I. Cohen, A Report on the Pogroms in Poland, Central Office of the Zionist Organization, Londyn 1919.

² Z.Razowski, Relacje polsko-żydowskie w Chrzanowie i okolicy w latach 1918-1923 jako przyczynek do badań nad Szoa, s. 183.

³ Konrad Meus, When cordons broke and borders were born… Western Galicia Province in November 1918, “Folia Historica Cracoviensia” 2022, t. 28, nr 1, s. 47-48. Zob. także: W.W. Hagen, Anti-Jewish Violence in Poland, 1914-1920, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2018, s. 125-127.

Berlin, 1934, recording by Robert J. Gessner; a section of the facade of the synagogue at Grenadierstraße 32.

WATCH THE RECORD – Source: Collections Search – United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (ushmm.org)

However, Hirsh Leib Bakon regards this period as a transitional one – despite comfortable living conditions (a five-room apartment), he feels alienated and lacks a sympathetic Chrzanow audience. In Berlin he is accompanied only by his two sons, Jankiel and Israel. Although, according to Chrzanow resident Berek Grajower (1922-?), Bakon decides to return to Chrzanow driven by local patriotism (“they wanted [him] to be permanently employed in Berlin, but he loved Chrzanow and wanted to live here”⁴), there may be more reasons. One of them is certainly the desire for “his sons to remain Jewish”⁵ – to avoid “the temptations of the big city” and “deviate from the Hasidic path”⁶.

Hirsh Leib returns to Chrzanów together with his relatives in 1923. For the duration of the renovation of the apartment in Hirsz Wiener’s house on Krakowska Street, which consisted of a room, a kitchen and an attic, the various members of the family separate and for about a year they live in friendly houses. In 1924, they can already stay under one roof. The time that follows, Yitzhak Bakon recalls as follows:

The year was divided into two parts. In the weeks leading up to the holidays, the apartment was filled with choristers (Hebrew: Meshorerim) and enthusiasts of [his father]. The adults occupied the chairs and beds, while the younger boys stood or sat on the floor. In the days before the holidays, crowds gathered in the street.

“Between the holidays,” the atmosphere in the house would calm down, but only a little. It was a time for composing and creating. Day after day, melodies developed and blossomed on the pages. At night, my father had conversations with friends. […] I don’t think the people who gathered in our small apartment had much in common. Some were music lovers who had known my father since childhood, but others adored him and sought his company for entirely different reasons. […] During these gatherings, verses from the Torah were recited, […] and discussions about cantors took place. […] Some evenings were devoted entirely to music. […]⁷.

⁴ W pamięci i w sercu – Chrzanów we wspomnieniach Berka Grajowera, „Chrzanowskie zeszyty muzealne” 2001, tom III, s. 84.

⁵ Bakon, Author’s Note, w: tegoż, Hazzan Reb Hirsh Leib Bakon, przeł. Y.B., Josephine Bacon, Roy Abramovitz, Mezmeret Ḳshanuv, Pholiota Press, Izrael-Londyn 1991, s. 12.

⁶ H.J.P. Bergmeier [et al.], Beyond Recall: A Record of Jewish Musical Life in Nazi Berlin – 1933-1938/Vorbei: Dokumentation jüdischen Musiklebens in Berlin – 1933-1938, Bear Family Records, Hambergen 2001.

⁷ Y. Bakon, Author’s Note, s. 14-15.

The daily routine of Hirsz Lejb Bakon was almost entirely dedicated to creating music and studying the Gemara. He spent his days at home, composing and humming melodies, always keeping his sheet music and Gemara within reach. Sometimes he would interrupt his work, ask his wife for twenty groszy, and send his son, Icchak, to buy cigarettes. In the evenings, at the beit ha-midrasz, he would read the Gemara and Tosafot with young Jewish students.

In 1928, his health declined, and he traveled to Berlin for treatment, bid farewell by crowds gathered on the street. He soon returned with a cancer diagnosis. He died on March 25, 1928, in Chrzanów, where he was buried.

In 2007, his damaged gravestone was found and identified by Wojciech Wyziński, the Community Guardian of Monuments in Chrzanów, who is responsible for, among other things, the Jewish Cemetery. Like many other gravestones in the Chrzanów cemetery, it has since been restored.

According to Mordechai Bochner, author of the book of remembrance of the Chrzanow Jews, Hirsh Leib Bakon was both “a scholar, a musical genius, a great holdentenor and a prolific composer”⁸, whose funeral compositions have been compared to Chopin’s Funeral March.

Musicologist Professor Eliyahu Schleifer, on the other hand, argues that in Hirsh Leib Bakon’s compositions meet his “personality, Hasidic faith […], high musical sensitivity, weakness for interesting and complex melodies, and above all: creativity and originality”⁹. Emotional depth and religious content were the hallmarks of music that appealed not only to professional cantors, but also to ordinary people “humming it in their homes”¹⁰.

⁸ Bochner, Chrzanów: The Life and Destruction of a Jewish Shtetl, Solomon Gross, Nowy Jork 1989, s. 30.

⁹ E. Schleifer, Prof. Y. Bakon’s Book on the Music of R. Hirsh Leib Bakon, w: Y. Bakon, Hazzan…, b.p.

¹⁰ Schleifer, Prof. Y. Bakon’s Book…, b.p.

ISRAEL BAKON (1910-1943)

cantor, chazan, Chrzanow resident

Israel Bakon is born in Chrzanów, Poland, in 1910, and after the family moves to Berlin, he studies at Rabbi Halberstam’s yeshiva and sings in his father’s choir. Israel’s fascination with concerts, opera, circuses and amusement parks far disturbs Hirsh Leib, who – unlike his son – does not find his way in the big city. The decisive reason for leaving Berlin and returning to Chrzanów is supposed to be his father’s objectionable proposal that Israel sing his piece Lo Tevoshi [Don’t be afraid] in one of the Jewish theaters.

In Poland, Israel continued his education at yeshivas in Trzebinia and Bobowa. In 1931, as a twenty-one-year-old, he emigrates again: first to Kosice and then to Berlin. There he contributes to the Jewish Cultural Union (Jüdischer Kulturbund) and gains increasing recognition (he gives concerts in Antwerp, London and Hamburg, among other places).

In the German capital, the young Bakon meets Hirsh Levin (1892-1958), who was sent to Berlin as a civilian prisoner during World War I and remained there after its end. Having gained experience as a bookseller, in 1930 Lewin opens his own bookstore, on Grenadierstraße 28 (now: Almstadtstraße 10). Religious texts in Hebrew, historical works or children’s literature can be purchased there, as well as prayer shawls and Shabbat candles and, of particular interest, a selection of phonograph recordings.

Indeed, in 1932 The Semer Record Label (Hebrew: semer – song) was established, operating for the next five years and releasing “hit Yiddish songs, folk songs, opera arias and cantor music.”

The songs are performed in Yiddish, Hebrew, German, Russian and Italian. It is through Lewin’s label that the first album of Bakon, “a young cantor from eastern Galicia,” containing nearly thirty songs, is released in February 1936. He is accompanied on the piano by Arno Nadel (1878-1943), a Lithuanian musicologist, composer, poet and painter who would be murdered in Auschwitz during the war. Soon after the album’s release, Bakon sends the recordings to his relatives in the United States, so today we can hear them in their original sound.

In the early May 1937 issue of the Jewish weekly Israelitische Familienblatt, Micha Michalowitz describes the works performed by Israel Bakon as

“[…] extremely authentic, giving insight into the soul of the Jewish people, who lived and still live in their self-sufficient culture in the countries of Eastern Europe. The voice of […] [Bakon] is pure and full of youthful energy, yet tinged with the melancholy of thousands of years of suffering in exile”¹¹.

Although this description is not free of exoticizing tones, it demonstrates the enthusiastic reception of the work of the young Bakon, whom Hirsh Levin reportedly calls his “discovery.” Two years later, after the events of Kristallnacht – during which the bookstore on Grenadierstraße is completely destroyed – Israel, his wife Chaya and his only son, Hirsz, decide to return to Poland.

The outbreak of World War II prevents Bakon from taking a position as cantor at the Ahawat Raim house of prayer on Szpitalna Street.

Although descriptions of the subsequent fate of the three-member Bakon family vary depending on the source, from Krakow they most likely go to Kolbuszowa – in June 1941 the Nazis create a ghetto there. At the end of June 1942, all the Jews gathered in the Kolbuszowa ghetto are deported to nearby Rzeszow, and from there to the Belzec death camp.

Shortly after the mass deportation, a group of about a hundred Jews returned to Kolbuszowa to perform physical work related to the demolition of the ghetto. After their completion, in November 1942, they are transported successively to Rzeszow and Belzec.

Although it is difficult to reconstruct the circumstances in detail or establish a precise date, there is much to suggest that Israel Bakon and his family from Kolbuszowa ended up in the Tarnów ghetto, where the young cantor gives encouragement to the others with his singing.

In 1943, Yisrael, Chaja and little Hirsh are transported to the Belzec death camp and murdered – as were at least 434,000 other Jewish victims.

¹¹ Bergmeier H.J.P. [et al.], Beyond Recall: A Record of Jewish Musical Life in Nazi Berlin – 1933-1938/Vorbei: Dokumentation jüdischen Musiklebens in Berlin – 1933-1938, Bear Family Records, Hambergen 2001.

ICCHAK BAKON (1918-2013)

son of Hirsh Leib, brother of Israel, Chrzanow resident, professor of Yiddish and Hebrew literature, author of a book about his father.

Born in Chrzanow, Yitzhak Bakon spends the war in exile – in the USSR, in the Vang’ Ozierra gulag. As he writes in the book dedicated to his father, it was there, after finishing one of the evening roll calls, that Max Goldberg, who came from Alwernia, approached him and asked if his last name was really Bakon and if he knew Hirsh Leib, about whom he had heard so much from his grandfather.

Unlike Yitzhak Bakon, as a minor prisoner Goldberg avoids physical labor in the woods – he works for the camp commandant. Before being sent to another gulag, he will sometimes give Isaac his food coupon or share leftover food.

Soon after being drafted into the Soviet army, Yitzhak Bakon moves towards Ukraine and Poland; after the war ends, he is sent to the Friedland transit camp in Lower Saxony. During one of the seminars for Jewish children held there, he is once again asked by a stranger about his name and relationship to Hirsh Leib. This time the question falls from the mouth of Elek Stern from Cracow. Shortly before the outbreak of war, Stern copies several compositions by Hirsh Leib for Yosef Tilles, who is emigrating to the Land of Israel (Hebrew: Eretz Israel).

When Yitzhak and Elek arrive together at kibbutz En Gew, Elek finds Tilles and gives Bakon’s son copies of the musical compositions of the “cantor from Chrzanow.”

Although as a child Yitzhak sings in his father’s choir and often accompanies him, in adulthood he takes a completely different path: that of a non-practicing Hasid, a professor of Yiddish and Hebrew literature at Ben-Gurion University in Israel. He visits Chrzanow several times and dreams that his longtime friend, novelist and poet Aharon Appelfeld (1932-2018) will write a book about the city.

Although this literary project does not come to fruition, Yitzhak Bakon manages to realize another. In 1998, his publication Hazzan Reb Hirsch Leib Bakon is published, containing more than fifty musical notations with paternal compositions. Some of them survive in their original form, others as copies made by relatives or faithful disciples (women were not allowed to serve as cantors at the time), and still others Prof. Bakon notes from memory. In total, he recovers more than two hundred of them.

Some of them become an inspiration for the Slovak Mojše Band – which specializes in reinterpretations of traditional Jewish music – and British cantor Rachel Weston. They are performing the pieces composed for the project on recordings made available online and live at a special concert in Chrzanow.

Content development: Aleksandra Kumala

Compositions: Cantor Hirsz Lejb Bakon, Israel Bakon

We would like to express our gratitude to the following individuals/institutions for their assistance in the realization of this project:

- Anna Sadło-Ostafin (Muzeum im. Ireny i Mieczysława Mazarakich w Chrzanowie),

- Michael Simonson (Dr. Robert Ira Lewy Reference Service – Leo Baeck Institute),

- dr Michael Lukin (Jewish Music Research Centre)

- prof. em. Edwin Seroussi (Jewish Music Research Centre, Yale University)

- dr Amalia Kedem (Jewish Music Research Centre)

Sources:

- Kolbuszowa [broszura informacyjna], Muzeum i Miejsce Pamięci w Bełżcu, kolbuszowa.pdf (belzec.eu) (PL) | kolbuszowa_-_ang.pdf (belzec.eu) (ENG)

- Mes musiques régénérées (musiques-regenerees.fr)

- Israel Bakon (jewniverse.info)

- Kolbuszowski Magiel: Israel Bakon

- Jewish Museum Berlin: Special Exhibition “Berlin Transit” – Almstadtstr. 10 Berlin, Hebrew Bookstore (jmberlin.de)

- Encyclopaedia Judaica, t. 3, red. Fred Skolnik, Michael Berenbaum, Thomson Gale, Macmillan Reference USA, Detroit 2007.

- The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Music Studies, red.Tina Frühauf, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2023.

- Bergmeier H.J.P. [et al.], Beyond Recall: A Record of Jewish Musical Life in Nazi Berlin – 1933-1938/Vorbei: Dokumentation jüdischen Musiklebens in Berlin – 1933-1938, Bear Family Records, Hambergen 2001.

- W pamięci i w sercu – Chrzanów we wspomnieniach Berka Grajowera, „Chrzanowskie zeszyty muzealne” 2001, t. III.

- Hagen William W., Anti-Jewish Violence in Poland, 1914-1920, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2018.

- Bochner Mordechai, Chrzanów: The Life and Destruction of a Jewish Shtetl, Solomon Gross, Nowy Jork 1989.

- Cohen Israel, A Report on the Pogroms in Poland, Central Office of the Zionist Organization, Londyn 1919.

- Razowski Zbigniew, Relacje polsko-żydowskie w Chrzanowie i okolicy w latach 1918–1923 jako przyczynek do badań nad Szoa, w: Ciemności kryją ziemię: wybrane aspekty badań i nauczania o Holokauście, red. Martyna Grądzka-Rejak, Piotr Trojański, Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Pedagogicznego im. Komisji Edukacji Narodowej, Fundacja Nomina Rosae Ogród Kultury Dawnej, Kraków-Nowy Sącz 2019, s. 171-188.

- Wyzina Wojciech, Kierków: zabytek za kamiennym murem, Muzeum w Chrzanowie im. I. i M. Mazarakich Oddział “Dom Urbańczyka”, Chrzanów 2005.

- Meus Konrad, When cordons broke and borders were born… Western Galicia Province in November 1918, “Folia Historica Cracoviensia” 2022, t. 28, nr 1, s. 37-67.

- Żyli wśród nas: chrzanowscy Żydzi, red. Marek Szymaszkiewicz, Muzeum w Chrzanowie im. I i M. Mazarakich, Chrzanów 2016.

- Jeremiah Lockwood, Złoty wiek: Kantorzy i ich duchy | Festiwal Kultury Żydowskiej (jewishfestival.pl), przeł. Katarzyna Spiechlanin.

- Heller Wendy, Cantors – YIVO Encyclopedia

- Olivestone David, Cantorial Music | My Jewish Learning

- Muzyka żydowskich kantorów wraca do Polski | Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN w Warszawie

- Jewish Museum Berlin: Special Exhibition “Berlin Transit” – Almstadtstr. 10 Berlin, Hebrew Bookstore (jmberlin.de)

- Bakon Yitzhak, Hazzan Reb Hirsch Leib Bakon, przeł. Y.B., Josephine Bacon, Roy Abramovitz, Mezmeret Ḳshanuv, Pholiota Press, Izrael-Londyn 1991.

The event is co-organized by the Chrzanów Municipality, with partners including the Irena and Mieczysław Mazaraki Museum in Chrzanów, the Municipal Center for Culture, Sports, and Recreation, and the Public Library in Chrzanów.

Projekt finansowany w ramach Krajowego Planu Odbudowy i Zwiększania Odporności (KPO), wspieranego przez Unię Europejską w ramach funduszu NextGenerationEU.